Lesson 5 Adapted Primary Literature (APL) Concept-mapping: Complete the Consider phase of the CREATE method

180 minutes

There have been several different strategies used for entering the learning cycle to teach APLs, including the community-based reading approach, the PBL-approach and the science literacy approach (see more details on the right). We suggest using a fourth method. This involves employing concept mapping, which is embedded within a modified version of an inquiry-based learning framework, called the CREATE method (CREATE stands for Consider, Read, Elucidate the hypothesis, analyze the results and Think of the next Experiment). CREATE has been used successfully to teach undergraduate students how to read primary literature.

Techniques for entering the learning cycle to teach APLs: The community-based approach involves the entire class reading the APL together. Here the teacher acts as a facilitator to provide content expertise and provide metacognitive cues to help guide student learning and understanding. In the Problem-based learning approach, the teacher serves as a facilitator that provides some big picture problem, as well as other information needed to contextualize the APL research, but relies on students to define specific research problems and directions to address them. Following this, the teacher distributes the APL for students to read and discover what the scientists actually did. The science literacy approach relies on students reading an APL side-by-side with a secondary sourced news article that covers the same topic. Students then discuss structural and philosophical differences between the text prior to further discussion about the APL’s content.

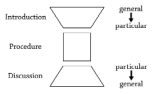

After entering the learning cycle, pass out a copy of a title-less, reference-less version of the APL that only contains the Introduction section. To guide student comprehension for reading the introduction, we suggest that prior to reading, the teacher should first outline the general logical flow and textual structure of primary literature (This could be achieved before this lesson, for example, by engaging students in the suggested activity listed in Lesson Two). The diagram shown below, re-printed from Norris et al 2015, is a good model to share with the students to depict the logical flow of scientific literature, including the introduction section.

Model for logical flow of scientific literature, with Introduction, Procedure, and Discussion section, moving from general to specific and then back to general

For example, by focusing specifically on the introduction section of the model, the teacher could use the following script to further clarify how the student should approach reading it:

Typical introduction sections in scientific literature begin with a birds-eye view perspective on a topic that contextualizes big-picture issues and problems; it then progresses towards explaining increasingly more specific issues/problems/concepts, eventually being resolved to specific research aims and questions that the scientists ended up pursuing in the paper

Below are a few things that students should reflect upon and use to regulate their learning as they read the introduction section:

- Why is the research important enough to merit government, industry, academic or private sector money to fund it?

Scientists need to be able to justify why their research matters and how it will serve an important service to society.

- Highlight key findings and questions that currently shape the state of the research field, including recent progress and unresolved issues. What do these aspects reflect about the nature of science?

Scientists do not aimlessly wonder around the lab and haphazardly conduct random experiments—rather the opposite is true: science requires crystalized ideas and focused planning that start and end on what other scientists have published.

- Identify the overarching experimental question(s) or goal(s), as well as a summary of the general approaches that were utilized to address them and what the research accomplished.

By the end of the introduction, the authors should have methodically provided the logic to set the stage for defining their central research hypothesis/question/goal, how they addressed them, as well as a general statement about what their research accomplished. Note that a detailed analysis of the study design is provided in the Materials and Methods section. - Brainstorm an appropriate title for the Introduction

The title should be a concise statement that summarizes the research findings.

After finishing reading the Introduction, students should engage in a concept mapping activity that follows the roadmap that they used and practiced during Lessons one and two: i) organize, ii) layout, iii) link, and iv) finalize the concept map. The concept map should include:

- a consolidated list of answers/thoughts to the reading discussion points outlined above

- a list of key terms and concepts that are essential for understanding the Introduction

- a title for the concept map (which should be a good fit for the title of the Introduction of the paper).

To scaffold the concept mapping activity, it is recommended that the Instructor highlight all of the essential concepts that the students should include in their concept maps, but let the students identify related and important vocabulary terms. This will ensure students spend their time wisely learning about key concepts (so that they can properly link them in their concept map), while also requiring them to take ownership over their own learning by having to identify key vocabulary that they think is relevant, or that they do not understand, to improve their overall understanding of the introduction section. To help facilitate concept mapping, the teacher could upload resources (i.e., web pages, PDF’s ect) to the Cmap-cloud that would be useful for exploring essential concepts in the introduction.

After completion, each group will share the results of their concept map (5-10 minutes/group). During and after each student presentation, the class should compare and contrast differences between groups in how they answered the reading questions, as well as how they defined and linked key terms/concepts within their concept maps.

Emphasize that there are different ways to conceptualize how to describe relationships amongst similar or identical concepts, as well as similar ways to conceptualize distinctly different concepts.

This type of creative reflection is useful for students to consider, as innovative thinking often involves repurposing a previous idea or product in a novel way to solve a related or unrelated problem. This also illustrates how there can be “more than one reasonable model” when it comes to defining and describing complex problems/issues/concepts. Yet, it is also critically important to provide feedback to students regarding the accuracy of their concept maps.

It is recommended that the teacher utilize his or her own concept map, as well as the lightening talk that was created during the CREATE-an-APL workshop to use as standard references for providing feedback to students.

Optional assessment: After finishing the discussion on the introduction section, students should study their concept map and class notes for homework to prepare for a small quiz on the introduction section prior to beginning Lesson Four.

Introduction section quiz (20 minutes)