print('Hello world!')Hello world!Programming today is a race between software engineers striving to build bigger and better idiot-proof programs, and the universe trying to produce bigger and better idiots. So far, the universe is winning. - Rick Cook

Programming is the art of solving a problem by developing a sequence of steps that make up a solution, and then very carefully communicating those steps to the computer. To program, you need to know how to

In this class, we’ll be using both R and Python, and we’ll be using these languages to solve problems that are related to working with data. At first, we’ll start with smaller, simpler problems that don’t involve data, but by the end of the semester, you will hopefully be able to solve some statistical problems using one or both languages.

It will be hard at first - you have to learn the vocabulary in both languages in order to be able to put commands into logical “sentences”. The problem solving skills are the same for all programming languages, though, and while those are harder to learn, they’ll last you a lifetime.

I particularly like the way that Python for Everybody (Severance 2016) explains vocabulary:

Unlike human languages, the Python vocabulary is actually pretty small. We call this “vocabulary” the “reserved words”. These are words that have very special meaning to Python. When Python sees these words in a Python program, they have one and only one meaning to Python. Later as you write programs you will make up your own words that have meaning to you called variables. You will have great latitude in choosing your names for your variables, but you cannot use any of Python’s reserved words as a name for a variable.

When we train a dog, we use special words like “sit”, “stay”, and “fetch”. When you talk to a dog and don’t use any of the reserved words, they just look at you with a quizzical look on their face until you say a reserved word. For example, if you say, “I wish more people would walk to improve their overall health”, what most dogs likely hear is, “blah blah blah walk blah blah blah blah.” That is because “walk” is a reserved word in dog language. Many might suggest that the language between humans and cats has no reserved words.

The reserved words in the language where humans talk to Python include the following:

and del global not with

as elif if or yield

assert else import pass

break except in raise

class finally is return

continue for lambda try

def from nonlocal while That is it, and unlike a dog, Python is already completely trained. When you say ‘try’, Python will try every time you say it without fail.

We will learn these reserved words and how they are used in good time, but for now we will focus on the Python equivalent of “speak” (in human-to-dog language). The nice thing about telling Python to speak is that we can even tell it what to say by giving it a message in quotes:

print('Hello world!')Hello world!And we have even written our first syntactically correct Python sentence. Our sentence starts with the function print followed by a string of text of our choosing enclosed in single quotes. The strings in the print statements are enclosed in quotes. Single quotes and double quotes do the same thing; most people use single quotes except in cases like this where a single quote (which is also an apostrophe) appears in the string.

R has a slightly smaller set of reserved words:

if else repeat while

for in next break

TRUE FALSE NULL Inf

NA_integer_ NA_real_ NA_complex_ NA_character_

NaN NA function ...In R, the “Hello World” program looks exactly the same as it does in python.

print('Hello world!')[1] "Hello world!"In many situations, R and python will be similar because both languages are based on C. R has a more complicated history, because it is also similar to Lisp, but both languages are still very similar to C and run C or C++ code in the background.

R and python both have an “interactive mode” that you will use most often. In the previous chapter, we talked about scripts and markdown documents, both of which are non-interactive methods for writing R and python code. But for the moment, let’s work with the interactive console in both languages in order to get familiar with how we talk to R and python.

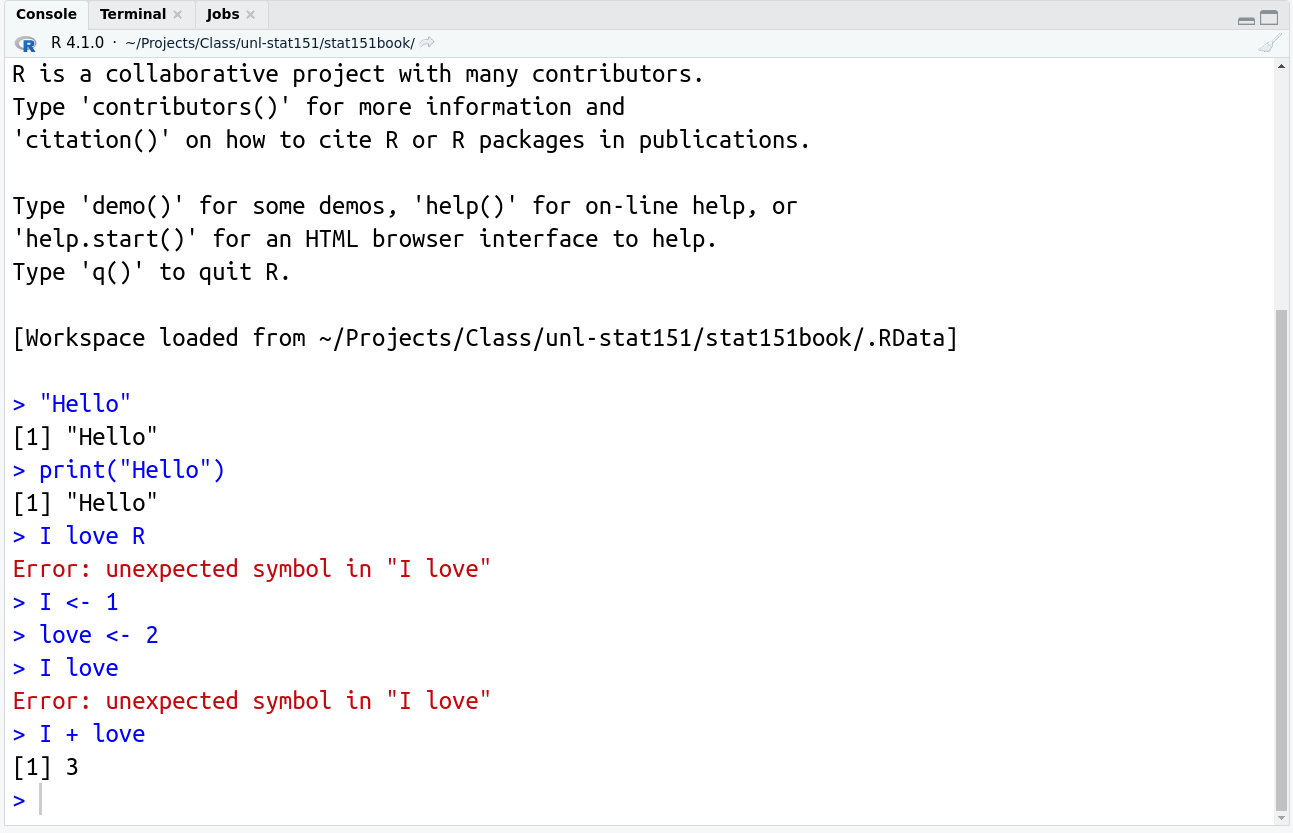

Let’s start by creating a Qmd file (File -> New File -> Quarto Document) - this will let us work with R and python at the same time.

Add an R chunk to your file by typing ```{r} into the first line of the file, and then hit return. RStudio should add a blank line followed by ```.

Add a python chunk to your file by typing ```{python} on a blank line below the R chunk you just created, and then hit return. RStudio should add a blank line followed by ```.

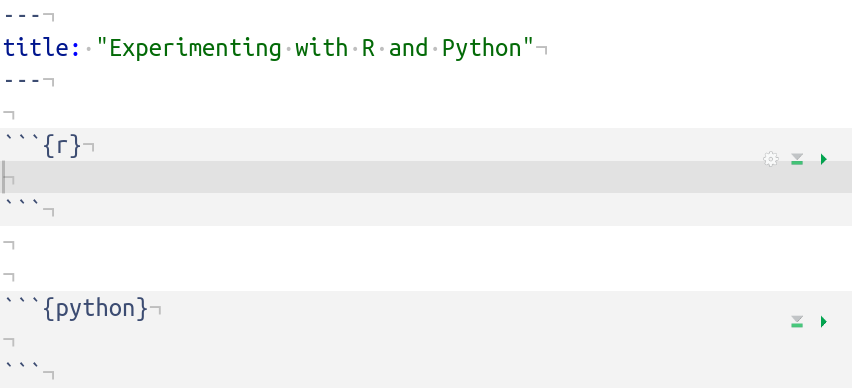

Your file should look like this:

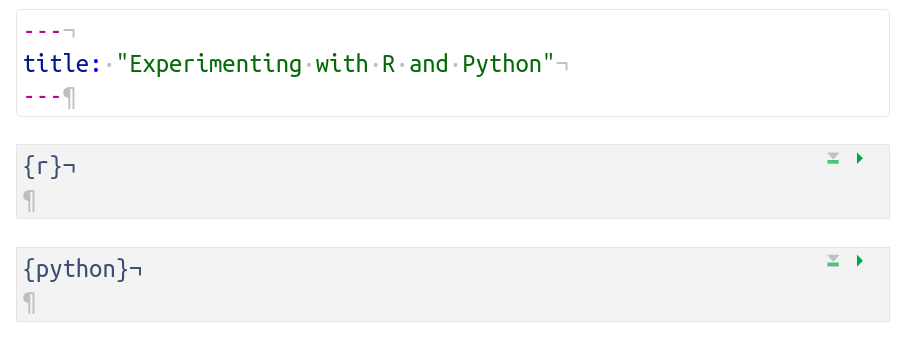

If instead your file looks like this:

you have visual markdown mode on. To turn it off, click on the A icon at the top right of your editor window:

If we are working in interactive mode, why did I have you start out by creating a markdown document? Good Question! RStudio allows you to switch back and forth between R and python seamlessly, which is good and bad - it’s hard to get a python terminal without telling R which language you’re working in! You can create a python script if you’d prefer to work in a script instead of a markdown document, but that would involve working in 2 separate files, which I personally find rather tedious.

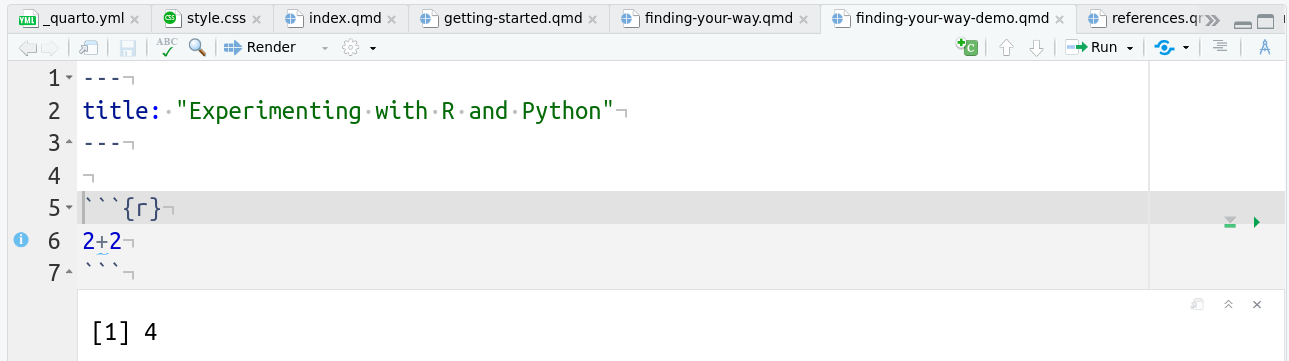

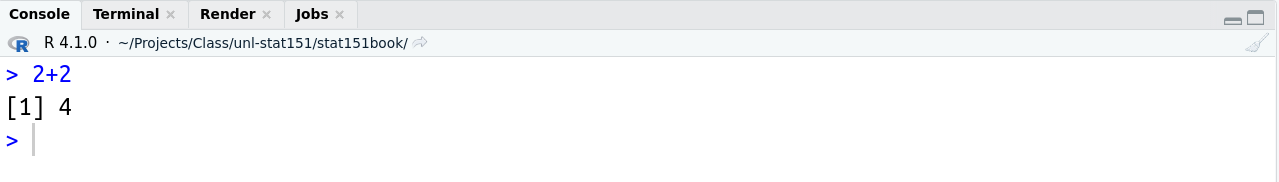

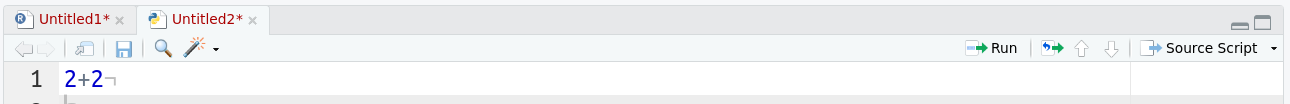

In your R chunk or script, type in 2+2 and hit Ctrl+Enter (or Cmd+Enter on a mac). Look down to the Console (which is usually below the editor window) and see if 4 appears. If you’re like me, output shows up in two places at once:

| Location | Picture |

|---|---|

| Chunk |  |

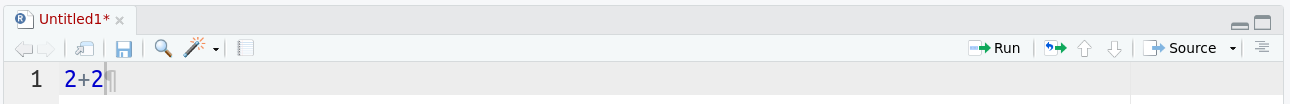

| Script |  |

| Console |  |

R will indicate that it is waiting for your command with a > character in the console. If you don’t see that > character, chances are you’ve forgotten to finish a statement - check for parentheses and brackets.

When you are working in an R script, any output is shown only in the console. When you are working in an R code chunk, output is shown both below the chunk and in the console.

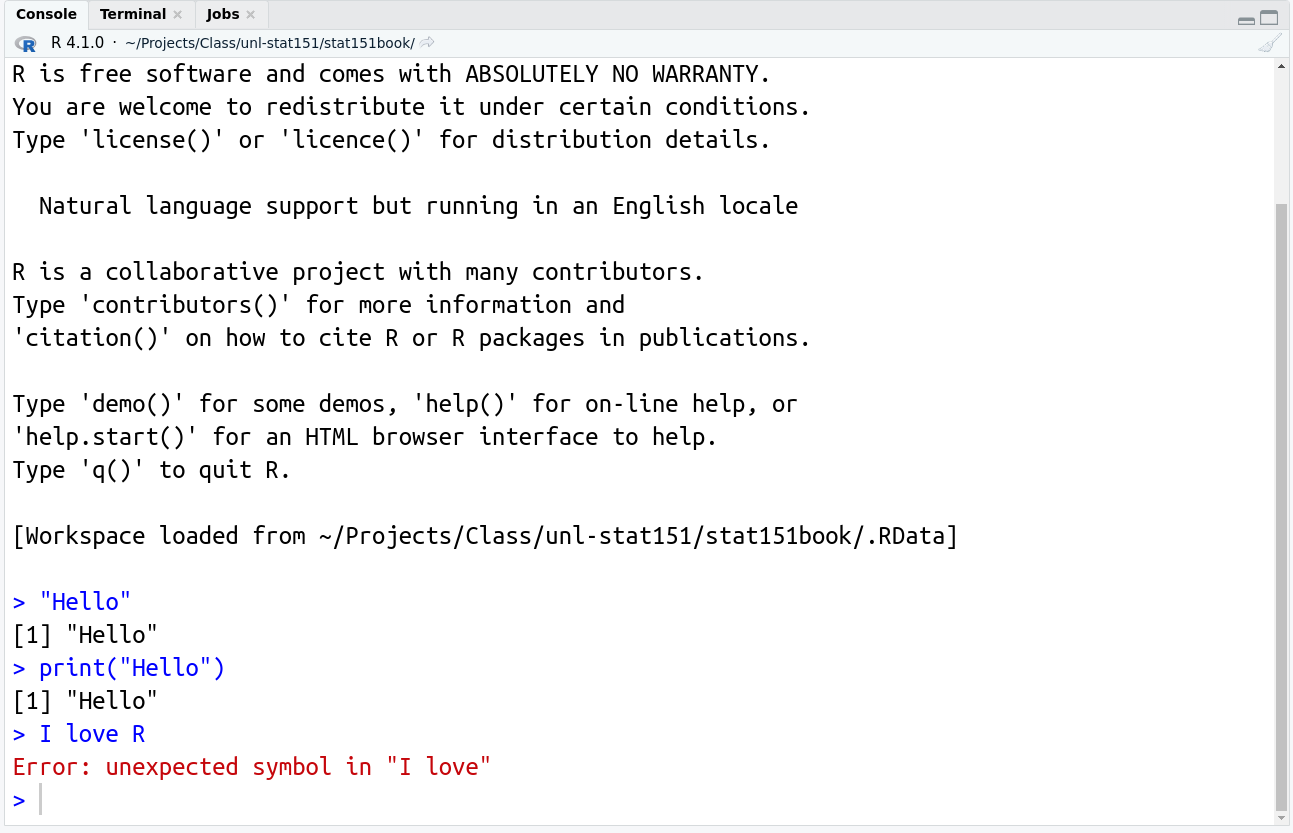

If you want, you can also just work within the R console. This can be useful for quick, interactive work, or if, like me, you’re too lazy to pull up a calculator on your machine and you just want to use R to calculate something quickly. You just type your R command into the console:

The first two statements in the above example work - “Hello” is a string, and is thus a valid statement equivalent to typing “2” into the console and getting “2” back out. The second command, print("Hello"), does the same thing - “Hello” is returned as the result. The third command, I love R, however, results in an error - there is an unexpected symbol (the space) in the statement. R thinks we are telling it to do something with variables I and love (which are not defined), and it doesn’t know what we want it to do to the two objects.

Suppose we define I and love as variables by putting a value into each object using <-, which is the assignment operator. Then, typing “I love” into the console generates the same error, and R tells us “hey, there’s an unexpected symbol here” - in this case, maybe we meant to add the two variables together.

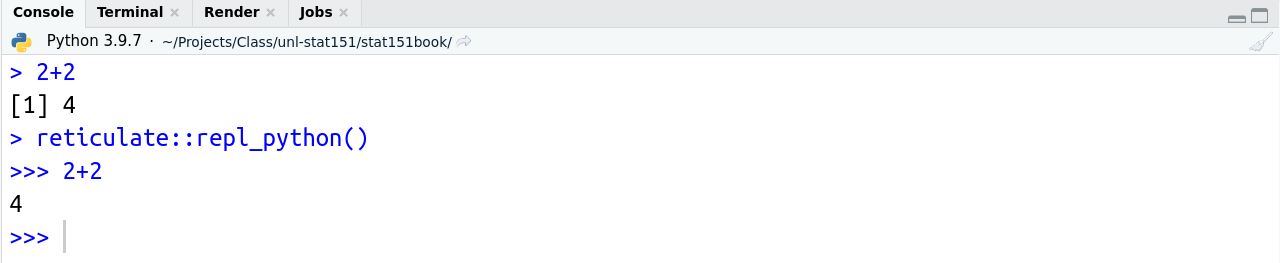

In your python chunk or script, type in 2+2 and hit Ctrl+Enter (or Cmd+Enter on a mac). Look down to the Console (which is usually below the editor window) and see if 4 appears. If you’re like me, output shows up in two places at once:

| Location | Picture |

|---|---|

| Chunk |  |

| Script |  |

| Console |  |

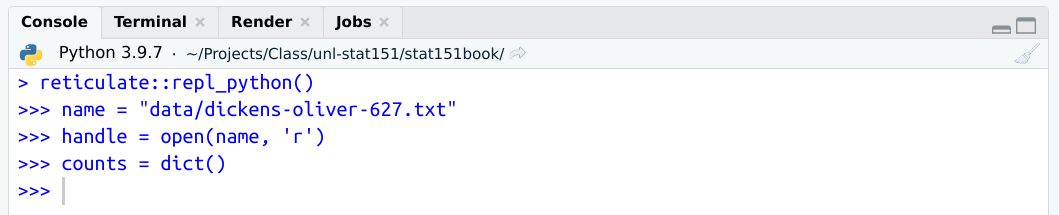

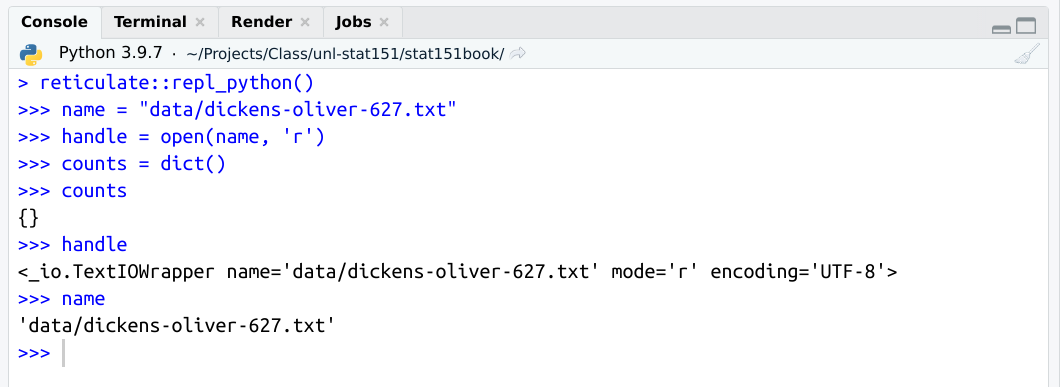

Notice that in the console, you get a bit of insight into how RStudio is running the python code: we see reticulate::repl_python(), which is R code telling R to run the line in Python. The python console has >>> instead of > to indicate that python is waiting for instructions.

Notice also that the only difference between the R and python script file screenshots is that there is a different logo on the documents:  . Personally, I think it’s easier to work in a markdown document and keep my notes with specific chunks labeled by language when I’m learning the two languages together, but when you are writing code for a specific project in a single language, it is probably better to use a script file specific to that language.

. Personally, I think it’s easier to work in a markdown document and keep my notes with specific chunks labeled by language when I’m learning the two languages together, but when you are writing code for a specific project in a single language, it is probably better to use a script file specific to that language.

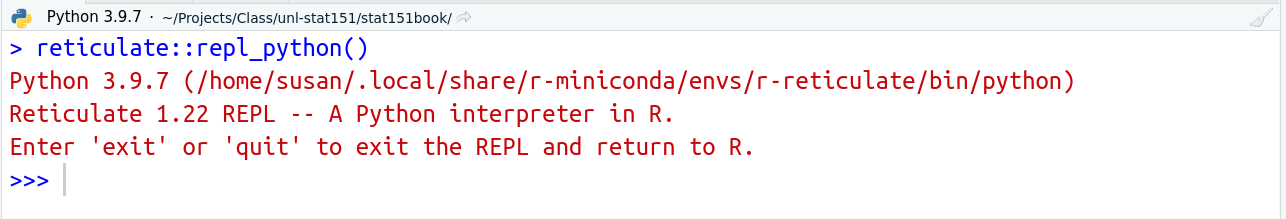

If you want to start the python console by itself (without a script or working in a markdown document), you can simply type reticulate::repl_python() into the R console.

R is nice enough to remind you that to end the conversation with python, you just need to type “exit” or “quit”.

If you want to start a python console outside of RStudio, bring up your command prompt (Darwin on mac, Konsole on Linux, CMD on Windows) and type python3 into that window and you should see the familiar >>> waiting for a command.

In the last chapter, we played around with scripts and markdown documents for python and R. In the last section, we played with interactive mode by typing R and python commands into a console or running code chunks interactively using the Run button or Ctrl/Cmd + Enter (which is the keyboard shortcut).

You may be learning to program in R and python because it’s a required part of the curriculum, but hopefully, you also have some broader ideas of what you might do with either language - process data, make pretty pictures, write a program to trigger the computer uprising…

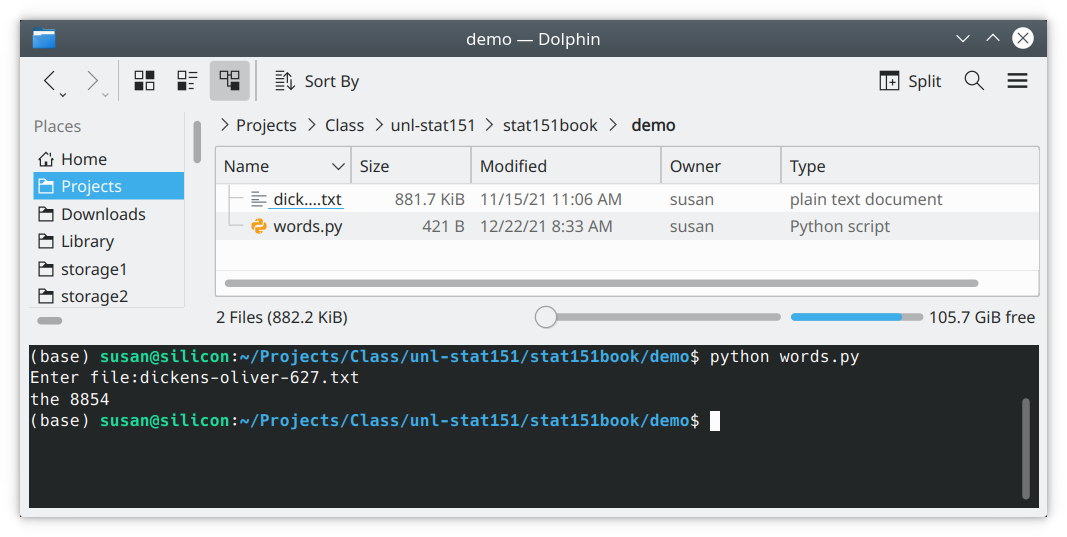

Scripts are best used when you have a thing you want to do, and you will need to do that thing many times, perhaps with different input data. Suppose that I have a text file and I want to pull out the most common word in that file. In the next few examples, I will show you how to do this in R and python, and at the same time, demonstrate the difference between interactive mode and script mode in both languages. In each example, try to compare to the previous example to identify whether something is running as a full script or in interactive mode, and how it is launched (in R? at the command line?).

Severance (2016) provides a handy python program to count words. This program is meant to be run on the command line, and it will run for any specified text file.

::: ex

Download words.py to your computer and open up a command line terminal in the location where you saved the file.

Before you run the script, save Oliver Twist to the same folder as dickens-oliver-627.txt (you can use another file name, but you will have to adjust your response to the program)

name = input('Enter file:')

handle = open(name, 'r')

counts = dict()

for line in handle:

words = line.split()

for word in words:

counts[word] = counts.get(word, 0) + 1

bigcount = None

bigword = None

for word, count in list(counts.items()):

if bigcount is None or count > bigcount:

bigword = word

bigcount = count

print(bigword, bigcount)

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/words.pyIn your terminal, type in python words.py. If all goes well, you should get a prompt that tells you to enter a file name. Type in dickens-oliver-627.txt, and the program will read in the file and execute the program according to the instructions shown above. You don’t need to understand what is happening in this program (just like you don’t need to understand what is happening in the R code above either) – you get the answer anyways: the most common word, according to the output from the program, is

the 8854That is, the word the occurs 8854 times in the text.

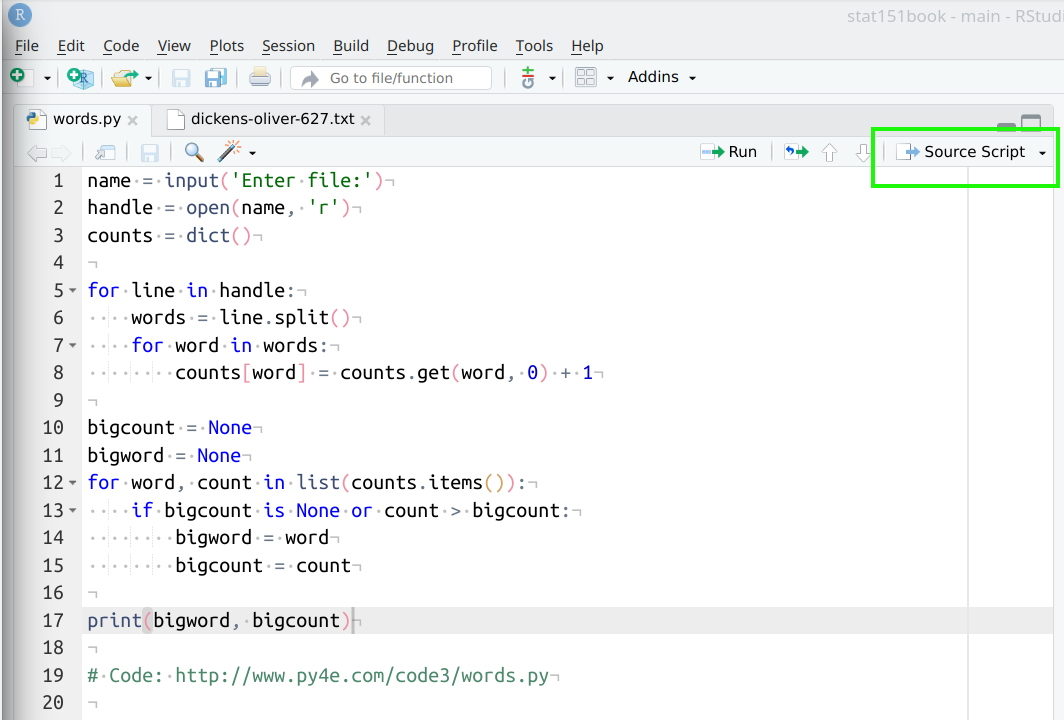

We can run this script in interactive mode in RStudio if we want to: Open the words.py file you downloaded in RStudio.

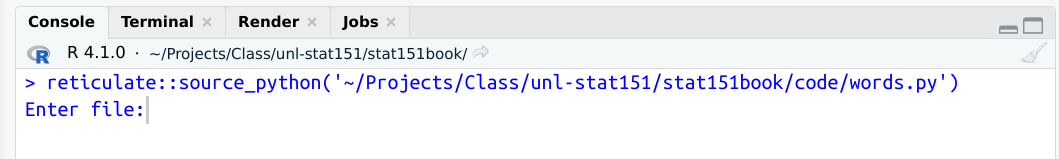

Click the “Source Script” button highlighted in green above, and then look at the console below the script window:

Once you enter the path to the text file – this time, from the project working directory – you get the same answer. It can be a bit tricky to figure out what your current working directory is in RStudio, but in the R console you can get that information with the

Once you enter the path to the text file – this time, from the project working directory – you get the same answer. It can be a bit tricky to figure out what your current working directory is in RStudio, but in the R console you can get that information with the getwd() command.

Since I know that I have stored the text file in the data subdirectory of the stat151book folder, I can type in data/dickens-oliver-627.txt and the python program can find my file.

In the above example, RStudio is functioning essentially like a terminal window - it runs the script as a single file, and once it has your input, all commands are executed one after the other automatically. This is convenient if you want to test the whole block of code at once, but it can be more useful to test each line individually and “play” with the output a bit (or modify code line-by-line).

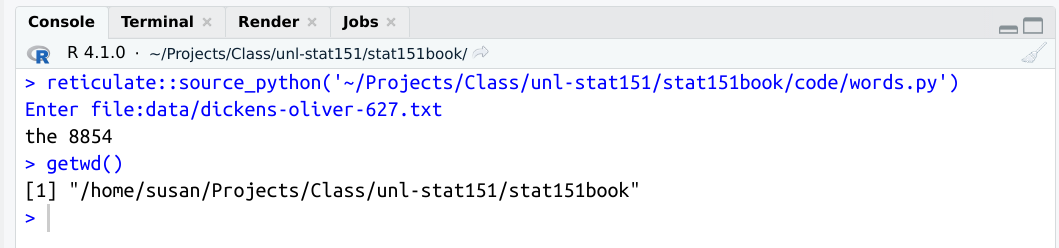

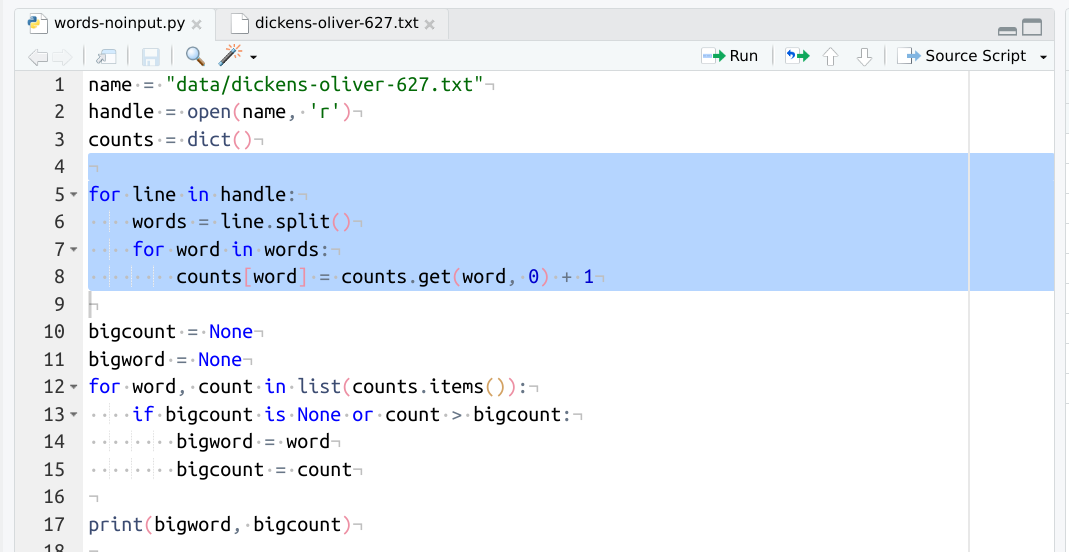

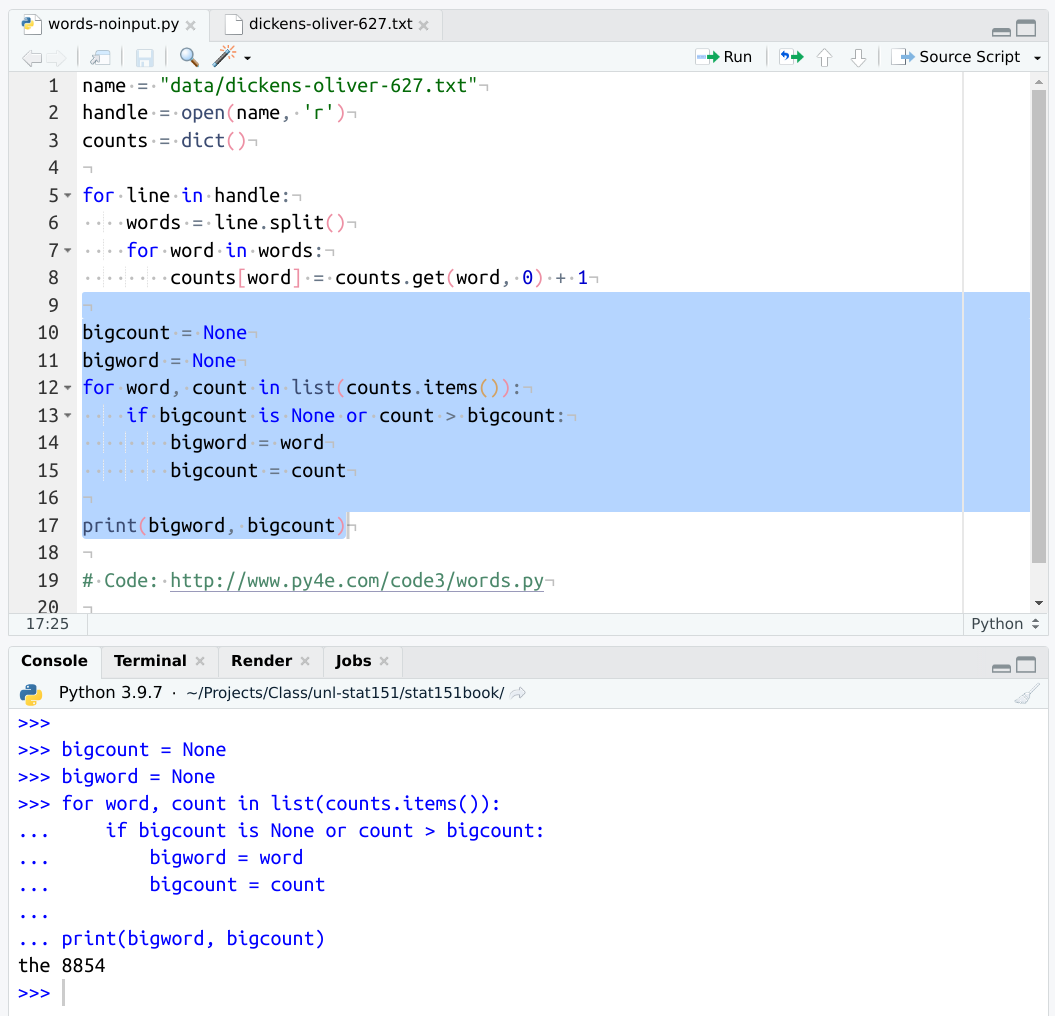

Suppose we want to modify this python script to be more like the R script, where we tell python what the file name is in the file itself, instead of waiting for user input at the terminal.

Instead of using the input command, I just provide python with a string that contains the path to the file. If you have downloaded the text file to a different folder and RStudio’s working directory is set to that folder, you would change the first line to name = "dickens-oliver-627.txt" - I have set things up to live in a data folder because if I had all of the files in the same directory where this book lives, I would never be able to find anything.

Create a new python script file in RStudio (File -> New File -> Python Script) and paste in the following lines of code, adjusting the path to the text file appropriately.

name = "data/dickens-oliver-627.txt"

handle = open(name, 'r')

counts = dict()

for line in handle:

words = line.split()

for word in words:

counts[word] = counts.get(word, 0) + 1

bigcount = None

bigword = None

for word, count in list(counts.items()):

if bigcount is None or count > bigcount:

bigword = word

bigcount = count

print(bigword, bigcount)

# Code: http://www.py4e.com/code3/words.pythe 8854

With the first 3 lines highlighted, click the Run button.

We can examine the objects that we have defined this far in the program by typing their names into the console directly.

We can examine the objects that we have defined this far in the program by typing their names into the console directly.

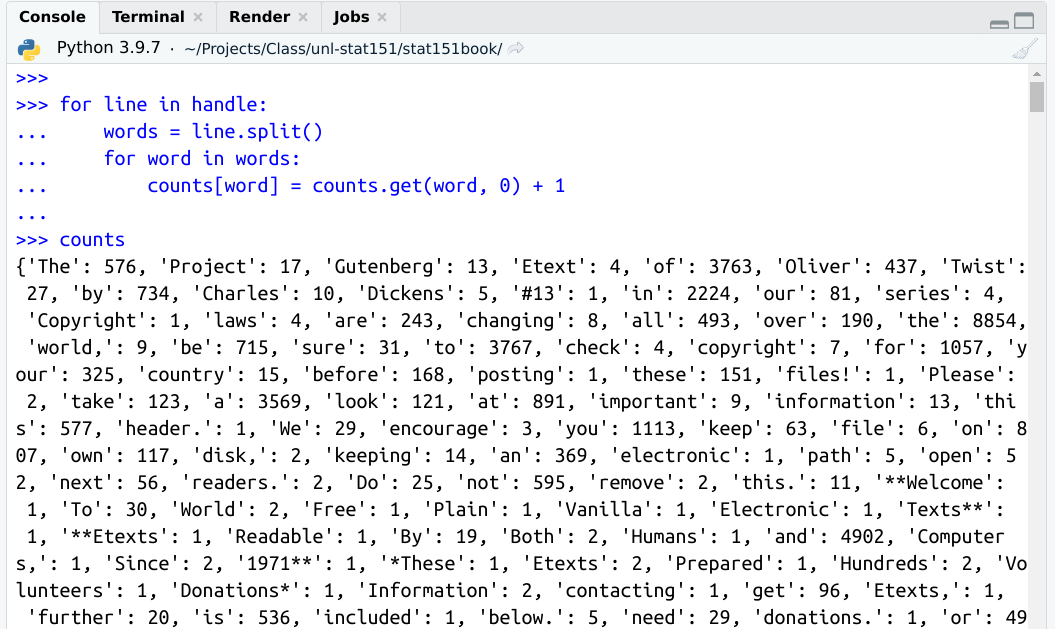

If we want to continue walking through the program chunk by chunk, we can run the next four lines of code. Lines 5-8 are a for loop, so we should run them all at once unless we want to fiddle with how the for loop works.

Select lines 5-8 as shown above, and click the Run button. Your console window should update with additional lines of code. You can type in counts after that has been evaluated to see what the counts object looks like now.

The next few lines of code determine which word has the highest count. We won’t get into the details here, but to finish out the running of the program, select lines 10-17 and run them in RStudio.

Running scripts in interactive mode or within RStudio is much more convenient if you are still working on the script - it allows you to debug the script line-by-line if necessary. Running a script at the terminal (like we did above) is sometimes more convenient if you have a pre-written script that you know already works. Both modes are useful, but for the time being you will probably be running scripts within your development environment (RStudio or VSCode or any other IDE you prefer) more often than at the command line.

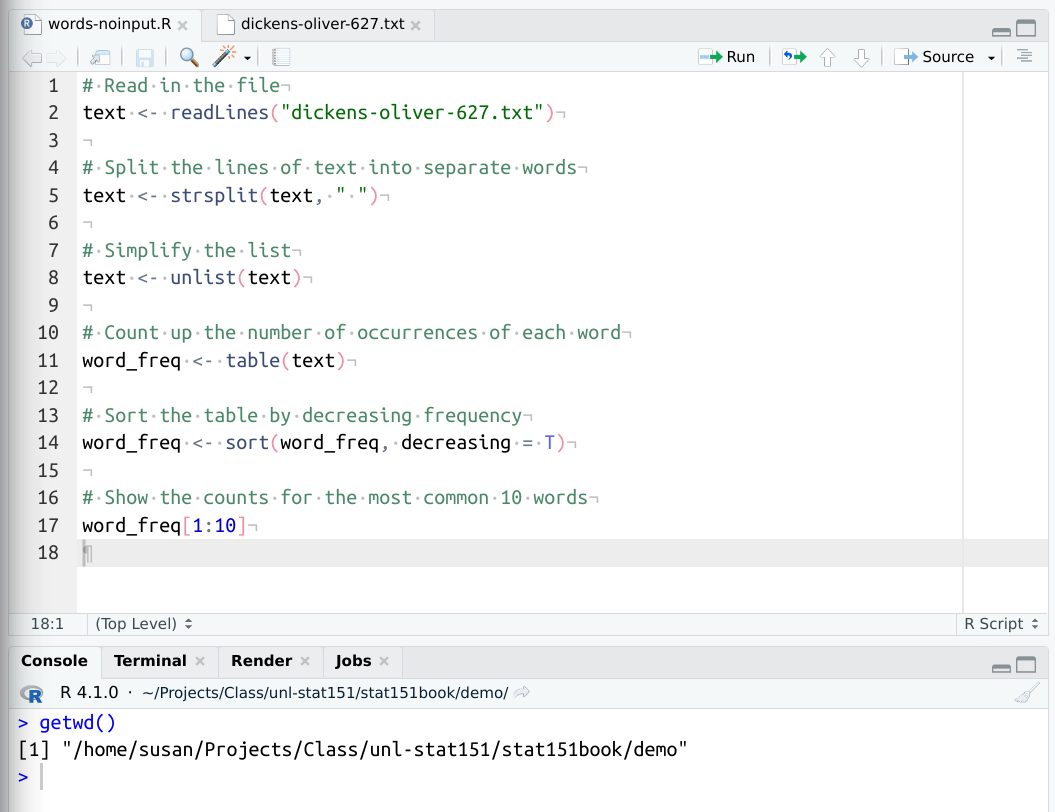

Just for fun, let’s work with Oliver Twist, by Charles Dickens, which I have saved here.

# Read in the file

text <- readLines("dickens-oliver-627.txt")

# Split the lines of text into separate words

text <- strsplit(text, " ")

# Simplify the list

text <- unlist(text)

# Count up the number of occurrences of each word

word_freq <- table(text)

# Sort the table by decreasing frequency

word_freq <- sort(word_freq, decreasing = T)

# Show the counts for the most common 10 words

word_freq[1:10]Make a new R script (File -> New File -> R script) and copy the above code into R, or download the file to your computer directly and open the downloaded file in RStudio.

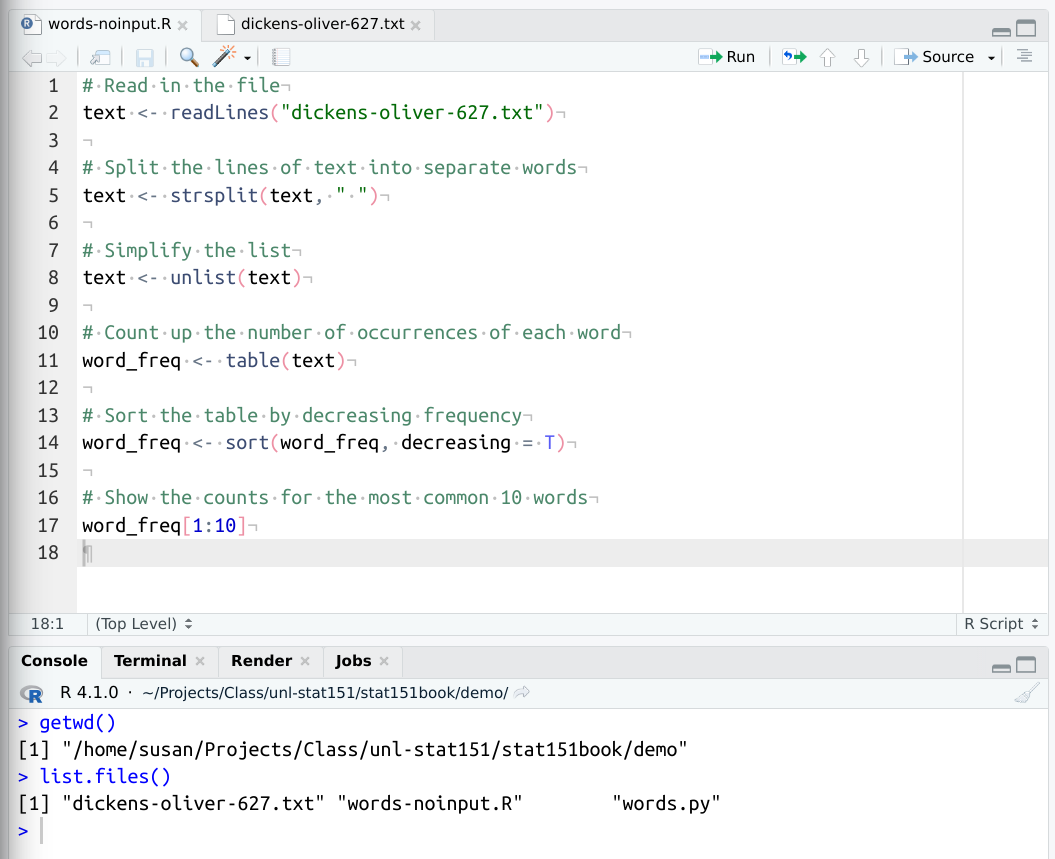

In the R console, run the command getwd() to see where R is running from. This is your “working directory”.

Save the copy of Oliver Twist to the file dickens-oliver-627.txt in the folder that getwd() spit out. You can test that you have done this correctly by typing list.files() into the R console window and hitting enter. It is very important that you know where on your computer R is looking for files - otherwise, you will constantly get “file not found” errors, and that will be very annoying.

Use the “Run” button to run the script and see what the output is. How many times does ‘the’ appear in the file?

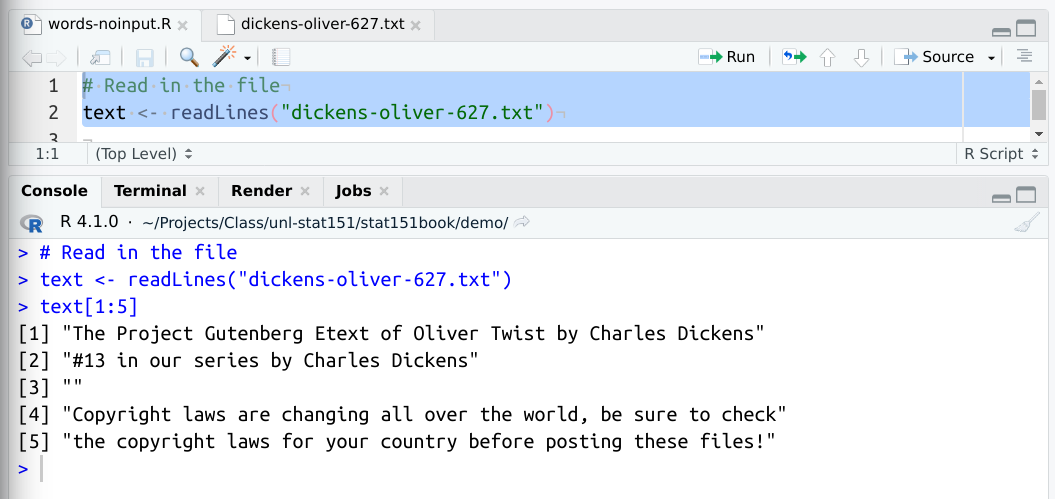

Using the file you created above, let’s examine what each line does in interactive mode.

# Read in the file

text <- readLines("dickens-oliver-627.txt")Select the above line and click the “Run” button in RStudio. Once you’ve done that, type in text[1:5] in the R console to see the first 5 lines of the file.

Run the next line of code using the run button (or click on the line of code and hit Ctrl/Cmd + Enter).

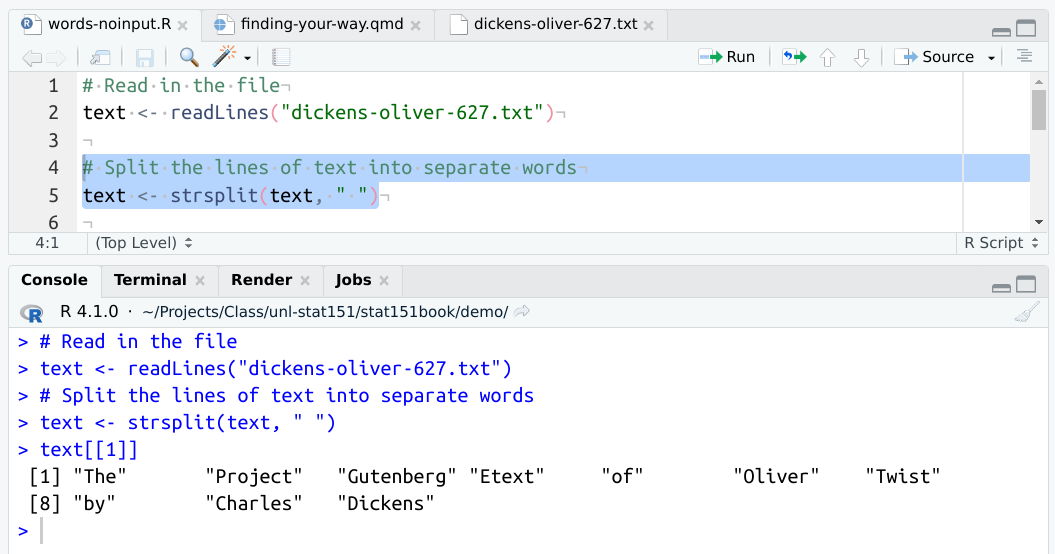

# Split the lines of text into separate words

text <- strsplit(text, " ")Type in text[[1]] to see what the text object looks like now.

text[[1]] [1] "The" "Project" "Gutenberg" "Etext" "of" "Oliver"

[7] "Twist" "by" "Charles" "Dickens"

# Simplify the list

text <- unlist(text)

text[[1]][1] "The"text[1:20] [1] "The" "Project" "Gutenberg" "Etext" "of" "Oliver"

[7] "Twist" "by" "Charles" "Dickens" "#13" "in"

[13] "our" "series" "by" "Charles" "Dickens" "Copyright"

[19] "laws" "are" Running unlist on text simplifies the object so that it is now a single vector of every word in the file, without regard for which line it appears on.

# Count up the number of occurrences of each word

word_freq <- table(text)

word_freq[1:5]text

_I_ --' --by --kneel

4558 4 1 1 1 The next line assembles a table of frequency counts in text. There are 4558 spaces, 4 occurrences of the string _I_, and so on.

# Sort the table by decreasing frequency

word_freq <- sort(word_freq, decreasing = T)

word_freq[1:5]text

the and to of

8854 4902 4558 3767 3763 We can then sort word_freq so that the most frequent words are listed first. The final line just prints out the first 10 words instead of the first 5.

Download the following file to your working directory: words.R, or paste the following code into a new R script and save it as words.R

# Take arguments from the command line

args <- commandArgs(TRUE)

# Read in the file

text <- readLines(args[1])

# Split the lines of text into separate words

text <- strsplit(text, " ")

# Simplify the list

text <- unlist(text)

# Count up the number of occurrences of each word

word_freq <- table(text)

# Sort the table by decreasing frequency

word_freq <- sort(word_freq, decreasing = T)

# Show the counts for the most common 10 words

word_freq[1:10]In a terminal window opened at the location you saved the file (and the corresponding text file), enter the following: Rscript words.R dickens-oliver-627.txt.

Here, Rscript is the command that tells R to evaluate the file, words.R is the R code to run, and dickens-oliver-627.txt is an argument to your R script that tells R where to find the text file. This is similar to the python code, but instead, the user passes the file name in at the same time as the script instead of having to wait around a little bit.

This is one good example of the difference in culture between python and R: python is a general-purpose programming language, where R is a domain specific programming language. In both languages, I’ve shown you how I would run the script by default first - in python, I would use a pre-built script to run things, and in R I would open things up in RStudio and source the script rather than running R from the command line.

This is a bit of a cultural difference – because python is a general purpose programming language, it is easy to use for a wide variety of tasks, and is a common choice for creating scripts that are used on the command line. R is a domain-specific language, so it is extremely easy to use R for data analysis, but that tends to take place (in my experience) in an interactive or script-development setting using RStudio. It is less natural to me to write an R script that takes input from the user on the command line, even though obviously R is completely capable of doing that task. More commonly, I will write an R script for my own use, and thus there is no need to make it easy to use on the command line, because I can just change it in interactive mode. Python scripts, on the other hand, may be written for a novice to use at the command line with no idea of how to write or modify python code. This is a subtle difference, and may not make a huge impression on you now, but it is something to keep in mind as you learn to write code in each language – the culture around python and the culture around R are slightly different, and this affects how each language is used in practice.

In both R and python, you can access help with a ? - the order is just slightly different.

Suppose we want to get help on a for loop in either language.

In R, we can run this line of code to get help on for loops.

?`for`Because for is a reserved word in R, we have to use backticks (the key above the TAB key) to surround the word for so that R knows we’re talking about the function itself. Most other function help can be accessed using ?function_name.

In python, we use for? to access the same information.

for?(You will have to run this in interactive mode for it to work in either language)

w3schools has an excellent python help page that may be useful as well - usually, these pages will have examples. A similar set of pages exists for R help on basic functions