30 Data Documentation

Objectives

- Understand the importance of data documentation for reproducibility and scientific validity

- Leverage existing data documentation to provide accurate citations, identify necessary data cleaning steps, and inform modeling decisions

- Write data documentation that supports data re-use and analysis reproducibility

30.1 Understanding Data About Data

Metadata is a word that breaks down “into data about data”. More specifically, metadata is information about how the data came to exist, how it is formatted, how it may be used, what has been done to modify it from the raw form, and so on.

As statisticians, metadata is critical - without understanding the provenance of the data, we cannot select an appropriate model, identify data cleaning strategies, and define the limitations of our analysis and conclusions. Without appropriate metadata, statisticians can’t really ethically do inference – you can’t generalize to a population if you don’t know how the sample was collected and what decisions were made between data collection and the cleaned data! Sometimes, data comes to us with only informal, verbally communicated metadata from a collaborator, but it is still metadata - it would be much better to write the metadata down during the verbal communication to ensure that the documentation exists and can be referenced by others.

In its simplest form, metadata can be a README file that accompanies the data. There are several slapdash, informal metadata files that accompany datasets in this textbook - short text files that exist mostly to remind me where I got the dataset and (if they’re more recent), how the data was collected and maybe some additional context - variable descriptions (if I had time and they were easily accessible), citation information, and so on. There absolutely should be more examples in the data folder of this textbook’s repository, but I haven’t found that many, which is perhaps evidence that metadata is always something we (I) can improve on, at both an individual dataset level and in generating metadata for all datasets.

Basic metadata includes elements like: - the source of the data - the data format - is it a CSV? JSON file? Available as either? - what variables are present? What are the units?

The next section will explore the full list of different elements of metadata, but it’s far from exhaustive. There are many types of data, and each type might have some additional useful metadata which will be of interest to someone using that dataset.

30.2 Elements of Data Documentation

When you are writing metadata for a data file in your custody (or if you’re a statistician or data scientist trying to impose order on your collaborator’s data), it can be important to consider what information you should include in the data documentation file. Ideally, each data table should be documented with a different file, though if there are only a few highly related tables, it might be appropriate to use a single file to document them all. In addition, the collection of data tables should include an overall documentation file describing the data set as a whole as well and providing links to the sub-documentation files. Ideally, there is a balance between too many README files and a massive README file that the reader has to scroll for hours through to find the necessary information.

The next sections describe important components of data documentation; most of these components are essential for at least one hierarchical level of data documentation if there are multiple documentation files, but for now, let us assume that there is only a single README file documenting perhaps one or two data files.

30.2.1 Descriptive Metadata

The first information to provide is the metadata describing the collection – the essentials, including a title, author(s), creation date, and purpose.

The title of the metadata should be descriptive – if your data are physiological measurements of captured jackalopes, you might want to title the data as “Morphometry of Live-Trapped Jackalopes (Lepus temperamentalus) in Southern USA”, providing the technical term for physiological measurements (“morphometry”), the data collection method (“live-trapped”), the species (“jackalope (Lepus temperamentalus)” – both the common and scientific names), and a location (southern USA) gives a level of detail that helps potential users determine whether the data are fit for purpose.

# Morphometry of Live-Trapped Jackalopes in the Southern Appalachian Region, USA

Authors:

- Brer Rabbitson

- Fred Adanko

Data collection locations:

- Westminister, SC

- Cataloochee, NC

- Mouth of Wilson, VA

- Hiawassee, GA

- Wautauga, TN

Data collected between 2023-04-06 and 2024-08-23 using live traps baited with brandy-soaked carrots.In the initial description of the data, this level of detail is sufficient – it might be necessary to add additional data collection protocols in a different section of the file or in a different file altogether.

The next section of the file should contain information about the files in the dataset and the variables contained within each file. Typically, this involves a list containing the column/field name, observation type (character, numeric, integer, logical), and units, if applicable.

If there are multiple datasets, then this information may be specified as a nested list, with each data file containing a list of columns or fields. In more complicated instances where there are multiple relational tables, it may be helpful to provide a data schema showing how different tables and variables relate to each other.

## Files

- `jackalope-morphometry.csv`

- Columns

- `id` (4-digit integer, WXYZ) where W indicates the collection site (1-5, in order as listed above), and XYZ indicates the observation from that collection site.

- `sex` (M or F) Sex of the rabbit, as identified from examination of external genitalia.

- `antler_length_left` (double) Length of the left antler, in cm, measured from the base where it protrudes from the skin to the tip, following the thickest branch at each junction. The tape should be held as closely as possible to the antler along the curved path.

- `antler_length_right` (double) Length of the right antler, in cm, measured from the base where it protrudes from the skin to the tip, following the thickest branch at each junction. The tape should be held as closely as possible to the antler along the curved path.

- `ear_length_left` (double) Length of the left ear, in cm, measured from the center of the base of the ear to the tip of the ear.

- `ear_length_right` (double) Length of the right ear, in cm, measured from the center of the base of the ear to the tip of the ear.

- `hind_foot_length_left` (double) Length of the left hind foot, in cm, measured from hock to tip of the longest toe.

- `hind_foot_length_right` (double) Length of the right hind foot, in cm, measured from hock to tip of the longest toe.

- `fore_foot_length_left` (double) Length of the left fore foot, in cm, measured from carpus to tip of the longest toe.

- `fore_foot_length_right` (double) Length of the right fore foot, in cm, measured from carpus to tip of the longest toe.

- `body_length` (double) Length of the rabbit's body, in cm, measured from bottom of the spine just above the tail to base of the skull.

- `muzzle_length` (double) Length of the rabbit's face, in cm, measured from between the base of the front of the ears to the tip of the nose.

- `weight` (double) Weight of the rabbit, in kg, measured using a spring scale with a fabric container holding the rabbit.

- Notes

- In some cases, sex determination can be difficult to determine without causing additional distress to the animal. In these cases, sex is coded as NA.

In some cases, it can be useful to include one or more images showing the specifics of data collection. Figure 30.1 provides a visual aid to communicate exactly how the antler measurements are taken. When images need to be interspersed with text, it may be preferable to use a markdown file for the README, rather than a plain-text file, so that HTML or PDF README files can be generated.

Additional notes might specify the precision of the data collection tool(s), standards for rounding, and more.

If materials were used or consumed during data collection, the README may specify batch numbers, sources of materials, and other information necessary to replicate the experiment.

Data should be provided in a plain-text format where possible, and an open, well-documented format when plain-text data is infeasible or impractical. Storing data in proprietary formats should be avoided, as software support is not guaranteed over a long time period (or even a relatively short period of 5 years!).

30.2.2 Administrative Metadata

When creating data documentation, it is important to consider licensing and use specifications. Consider whether the data should be usable for commercial purposes, and whether attribution should be required if the data is reused. [1] describes some of the licensing options available for data.

Clearly specifying who may use the data, for what purposes, and under what terms is an important part of ensuring that other researchers have the information to be able to reuse your data subject to restrictions that may be imposed by corporate partners, funding agencies, or collaborators.

30.2.3 Provenance Metadata

It is important to provide information about any transformations or preprocessing the data has been through. Providing the raw data, along with intermediate steps and code to enact the transformations, is extremely helpful, as it allows someone to replicate your analysis, but also allows for the possibility that they will make different decisions about how to work with the raw data. It is also important to document any changes which are made to the raw data. One way to do this is to check plain-text raw data into a version control repository and use commit messages to document changes and the reason for the change. It may also be useful to create a changelog, where changes to the raw data are documented in a specific text file, along with the date and the reason for the change.

30.2.4 Data Collection Procedure Metadata

As with anything, the art of data documentation is knowing what to include and what to exclude. When in doubt, it may be useful to document the details in separate files and allow the potential user of the data to determine what aspects of data collection might be relevant. Psychology studies used to document the exact brand of computer and monitor used to present the stimuli, along with screen resolution, size, driver information, and more. This list of information was probably overkill, but in some experiments, the screen frequency might have been important. When documenting the collection protocol for a dataset, it’s useful to make lists of factors which were controlled across trials, factors which were manipulated across trials, and incidental factors. For the jackalope morphology study, we could list these factors out as follows:

Controlled factors

- measurement protocol

- model of scale used, margin of error, etc. and calibration procedure

- procedure for measuring jackalope weight

- procedure(s) for measuring jackalope dimensions

- procedure for baiting and placing trap

Manipulated factors

- Location

- Trap placements for each location

Incidental factors

- Environment

- Associated weather information during data collection period

Obviously, documenting all of this can be a ton of work and may involve e.g. videos showing procedures and even additional datasets.

While I’ve obviously made up the jackalope example, there is a very nice sea otter morphometry dataset [2] that has excellent documentation.

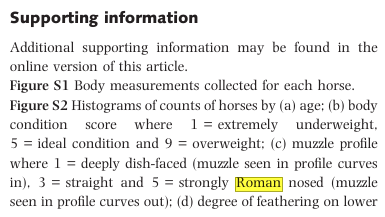

I reached out to a paper author about finding some morphometric data similar to palmerpenguins, because using the same dataset all the time can get tedious. In addition to the data I asked for, I got some bonus horse morphology data that was documented incredibly well, without needing to use a formal schema such as the one provided by DataCite.

Dr. Sutton (the paper author) provided 3 files: a fields.txt metadata file, the data itself, and the PDF of the paper describing the data.

Consider an excerpt of a few lines of the metadata file:

breed "Breed names, nomenclature typically follows breed clubs"

sex "M=mare, G=gelding, S=stallion"

AGE age in years at time of phenotyping

body_condition_score "larger values = heavier, judged subjectively by measurement-taker"

fore_shod yes/no

hind_shod yes/no

factor_dish_roman "See paper for details, factor scale 1-5 judged subjectively by measurement-taker"

factor_feather "See paper for details, factor scale 1-5 judged subjectively by measurement-taker"While not formally structured or delimited, this file is incredibly clear, and points to the paper for variables which cannot be adequately described in the text file.

factor_dish_roman variable in more detail.30.4 Tools and Standards

DataCite standards Data dictionaries README files codebooks

automated documentation systems??

30.5 Best Practices

- Version Control

- Documentation of processing and cleaning steps (and software, versions, environments)

- Logs of parameter settings and analysis code

- Links between data documentation and code documentation

30.6 Case Studies and Examples

Levels of documentation

Failed reproducibility efforts

Successful reproducibility efforts