1 Computer Basics

Before you learn how to program a computer, it can be helpful to learn a few basic things about how computers work. Modern computing environments hide most of the details about where and how files are stored from the user, but when you write computer programs, these details suddenly become important.

Objectives

Know the meaning of computer hardware and operating system terms such as hard drive, memory, CPU, OS/operating system, file system, directory, and system paths

Understand the basics of how the above concepts relate to each other and contribute to how a computer works

Understand the file system mental model for computers enough to identify where your files are stored

Locate and follow directions for software installation based on your computer’s hardware and operating system.

In this section, you will be identifying your computer’s specifications.

You will want to have a notebook or text file that you can reference later to record this information. Go ahead and determine where you will save this information now.

1.1 Hardware

The components that make up the physical computer are the hardware. This 3-minute video is focused on desktops, but the same components (with the exception of the optical drive) are commonly found in cell phones, smart watches, and laptops.

The important distinction for hardware is between Random Access Memoroy (RAM, or ‘memory’) and disk storage (hard drives). You can usually store much more on disk than you can have available in RAM, but when working with “big” data1, we must use different approaches than when working with data that can fit in memory.

We also need to know at least a little bit about processors (so that we know when we’ve asked our processor to do too much). For now, you are unlikely to challenge a modern processor when you first start learning R and Python, but as you acquire new skills, you may want to learn a bit about parallel processing (sending tasks to multiple processors). Most of the other details aren’t critical to programming with data just yet – graphics cards are important for some applications, but if you’re just learning R and python, you have a ways to go before you get there.

Examine the hardware on your computer using one of the following methods:

- Windows: Ctrl+Shift+Escape > Task Manager > More Options > Performance tab

- Mac: Apple menu > System Settings > General (sidebar) > About > System Report

- Linux: The

inxicommand will give you most of this on the command line, andhwinfo --shortwill give you a considerably more detailed printout.

Find out:

What processor do you have?

This most likely will start with ARM, Intel, AMD, or Apple M1How much RAM do you have? (most likely between 8 and 64 GB)

How much hard drive space do you have?

What graphics device do you have? (this might be slightly harder to find – it’s also less critical)

- Chapter 1 of Python for Everybody - Computer hardware architecture

1.2 Operating Systems

Operating systems, such as Windows, MacOS, or Linux, are a sophisticated program that allows CPUs to keep track of multiple programs and tasks and execute them at the same time.

Chances are, you can’t imagine doing computing without an operating system of some sort (and they’ve been ubiquitous on computers since the late 1980s). Even some appliances now have enough computing functions to require an operating system and an internet connection! Technically, you can use some Arduino and Raspberry Pi boards without an operating system2, but anything more complicated is almost guaranteed to have some minimal operating system available.

You should be able to identify your operating system (OS for short) and follow instructions based on that information. You will typically need to know not only the class of operating system (Windows/Mac/Linux) but also the version (e.g. Windows 11, Mac OSX Sierra, Debian 12, RedHat 7).

1.3 File Systems

File systems are, unsurprisingly, places you save files. They are modeled after physical file cabinets – individual documents are kept in a hierarchical sequence of folders. Ultimately, a collection of folders is stored on a drive.

Evidently, there has been a bit of generational shift as computers have evolved: the “file system” metaphor itself is outdated because no one uses physical files anymore, and new apps don’t show the user where on the computer their files are stored, forcing users to rely on the search feature instead of understanding file folders and paths. Dan Robitzski provided an interesting discussion of the problem, making the argument that with modern search capabilities, most people use their computers as a laundry hamper instead of as a nice, organized closet and dresser (or file cabinet) [1].

Regardless of how you tend to organize your personal files, it is probably helpful to understand the basics of what is meant by a computer file system – a way to organize data stored on a hard drive. Since data is always stored as 0’s and 1’s, it’s important to have some way to figure out what type of data is stored in a specific location, and how to interpret it.

1.3.1 Local and Network File Systems

It is important to distinguish between two primary types of file systems.

local file storage: files are stored on a physical disk contained within the machine you are actively using. A local file might be found at an address like

C:/Users/username/\ Documents/unnamed.txtor/home/users/username/Documents/unnamed.txtor/Users/username/Documents/unnamed.txt.network file storage, where files are stored “in the cloud” and you may have a link or a copy on your local machine.

Examples of network storage are Google Drive, Dropbox, Microsoft OneDrive, and iCloud. Organizations may have privately-hosted network file storage, but these services are still dependent on access to the internet and thus fall under network file storage.

If you have used primarily mobile devices or Chromebook-style laptops, then you have likely dealt primarily with network storage. When programming, it is essential to know where your files are being stored. You cannot conduct a file search to find your data and code (this is an interactive process). Instead, you will need to keep all of the files you need for a project together in a folder, and then keep track of where the project folder is stored.

Some operating systems (Windows, Mac OS) prefer to save files in network storage services that may (or may not) be also stored on your physical hard drive. Over time, it has become harder to ensure that you are working on a local machine, but working “in the cloud” can cause odd errors when programming and in particular when working with version control systems4

1.3.2 Allowed File Names

Different operating systems (and file system formats) have different rules for how file names are handled within the file system.

| Windows | Mac OSX | Linux | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disallowed Characters |

<, >, ", /, \, |, ?, *

|

:, some programs will restrict use of / . Avoid names that start with . unless the file should be hidden. |

NULL character, / . Can’t name files . or .. . Avoid \, ", ', *, ;, ?, [, ], (, ), ~, !, $, <, >, #, @, &, |, spaces, tabs, and newlines. Avoid names that start with . unless the file should be hidden. |

| Case Sensitive | No. A.jpg is the same as a.JPG

|

It’s complicated. Act as if it’s case sensitive to be safe. | Yes. A.jpg is different from a.jpg and A.JPG

|

| Name Length | Entire file path should be <256 characters5. | (For HFS+ systems) File names < 255 characters. File paths can be longer. | File names < 255 characters, File paths < 4096 characters (most file system options, including ext4) |

A Windows user saves a picture as my-pup.png and references the picture in a file as . The picture link works fine when compiled on the Windows machine, but causes an error when the folder is copied to a Linux server and compiled.

What do you think the error might look like?

What went wrong?

How can the user ensure that the picture link works on every operating system?

On the Linux machine the user will get a file not found error.

Windows is a case-insensitive operating system, so my-pup.png and My-pup.PNG will both point to the same file. Thus, when referencing the picture My-pup.PNG, the system finds my-pup.png and concludes they are the same file.

Linux is a case-sensitive operating system, which means that my-pup.png and My-pup.PNG point to different files. On Linux, the file reference is to My-pup.PNG, and the only file in the directory is my-pup.png, which doesn’t match the specified file name. Thus, Linux will raise a file not found error because the file My-pup.PNG does not exist on the system.

The user should reference my-pup.png instead of My-pup.PNG. This file name will work across all major operating systems.

1.3.3 File Paths

When you write a program, you may have to reference external files - data stored in data.csv, a diagram or picture, or a link to additional documentation.

To reference a file, you have to tell the computer where to look – that is, you have to give it a file path. File paths come in two basic types:

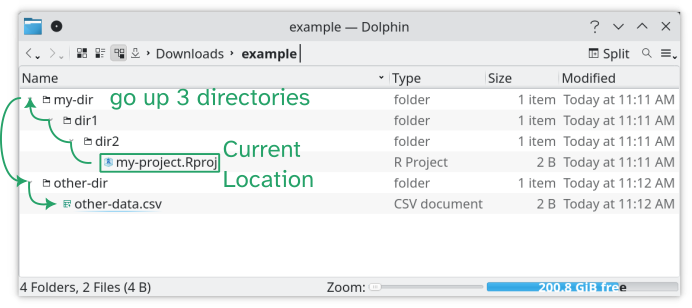

global file path: Starts at the file system location (e.g.

C:\or/homeor/Users) and describes how to navigate to the file.local file path: Starts at the program’s current location (the working directory) and navigates to the file from that point.

When you work on a project that may need to exist on some other machine, it’s important to use local file paths – the global path will likely not be the same, but you can usually set the local project-specific structure up to be the same across machines.

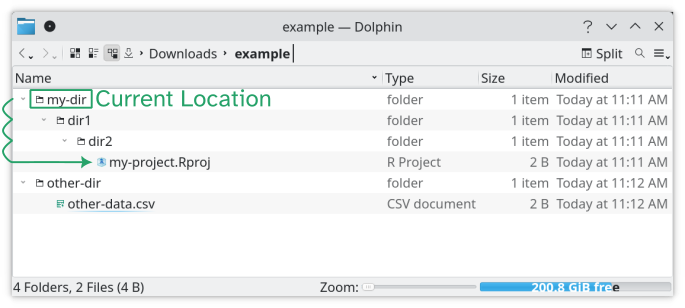

In fact, there’s a very common shortcut that programmers take – they set up a project-specific folder that is self contained. That is, all of the data and code necessary for that project is provided within the folder. Then, the code within the folder can use local paths and will work when the project folder is copied to a new machine.

To help with organization, it’s not uncommon to use a project structure like this:

- main-folder

- raw-data

- design.csv

- observations.csv

- other-vars.csv

- processed-data

- code

- 01-read-clean.xxx

- 02-analysis.xxx

- 03-simulation.xxx

- writeup.qmd

- README

- project-file.xxxThe README file contains a basic overview of the project’s contents. Files are added to the processed-data subfolder after code is run. Files in raw-data are set to read-only to prevent the data from being accidentally overwritten. A project-file.xxx file tells the program you’re using (RStudio, VSCode, Positron, etc) what the specific settings are, and also that this directory should be treated as the project root – that is, local file paths will start from this directory. When working on code, we will typically assume that the working directory (where the program looks for files) is main-folder.

[2] discusses several common layouts used for research projects.

1.3.3.2 Constructing File Paths

On Windows, file paths are constructed as follows: C:\Folder 1\Folder_2\file.R. Paths are generally not case sensitive, so you can reference the same file path as c:\folder 1\folder_2\file.R. Usually, paths are encased in "" because spaces make interpreting file paths complicated and Windows paths have lots of spaces.

On Unix systems, file paths are constructed as follows: /home/user/folder1/folder2/file.R. Paths are case sensitive, so you cannot reach /home/user/folder1/folder2/file.R if you use /home/user/folder1/folder2/file.r. On Unix systems, spaces in file paths must be escaped with \, so any space character in a terminal should be typed \ instead.

This quickly gets complicated and annoying when working on code that is meant for multiple operating systems. These complexities are why when you’re constructing a file path in R or python, you should use commands like file.path("folder1", "folder2", "file.r") or os.path.join("folder1", "folder2", "file.py"), so that your code will work on Windows, Mac, and Linux by default.

1.4 System Paths

When you install software, it is saved in a specific location on your computer, like C:/Program Files/ on , /Applications/ on , or /usr/local/bin/ on . For the most part, you don’t need to keep track of where programs are installed, because the install process (usually) automatically creates icons on your desktop or in your start menu that point to the right location.

Unfortunately, that isn’t sufficient when you’re programming, because you may need to know where a program is in order to reference that program – for instance, if you need to pop open a browser window as part of your program, you’re (most likely) going to have to tell your computer where that browser executable file lives.

To simplify this process, operating systems have what’s known as a “system path” or “user path” - a list of folders containing important places to look for executable and other important files. You may, at some point, have to edit your system path to add a new folder to it, making the executable files within that folder more easily available.

If you run across an error like this:

- could not locate xxx.exe

- The system cannot find the path specified

- Command Not Found

You might start thinking about whether your system path is set correctly for what you’re trying to do.

Let’s see what path errors look like using different tools you might encounter.

import pandas as pd

tmp = pd.read_csv("lego_sets.csv") # Wrong Path

## FileNotFoundError: [Errno 2] No such file or directory: 'lego_sets.csv'

tmp = pd.read_csv("../data/lego_sets.csv") # Right Pathhead -n5 lego_sets.csv

## head: cannot open 'lego_sets.csv' for reading: No such file or directoryIf you want to locate where an executable is found (in this example, we’ll use git), you can run where git on windows, or which git on OSX/Linux.

Some programs, like RStudio, have places where you can set the locations of common dependencies. If you go to Tools > Global Options > Git/SVN, you can set the path to git.

How to set system paths (general)

Operating-system specific instructions cobbled together from a variety of different sources:

Check out Section 41.1.1.2 for some basic shell commands in each operating system that will help you navigate your computer.

1.5 References

How big “big” is changes every couple of years – it used to be several GB circa 2010, and now it’s TB of data.↩︎

Chips and boards used without an operating system are often called “embedded systems”.↩︎

If you are using an operating system that is older, know that some of the installation instructions may require modification (but there are likely others online who have attempted something similar, so you can usually Google for how to adjust things when they don’t work).↩︎

To disable OneDrive sync for certain windows folders, use this guide. On Mac, see “Turn off Desktop and Documents” to stop iCloud sync of your Desktop and Documents folders (you can still manually copy things into iCloud for backup).↩︎

Longer paths can be enabled via registry edits if you’re brave/foolish.↩︎